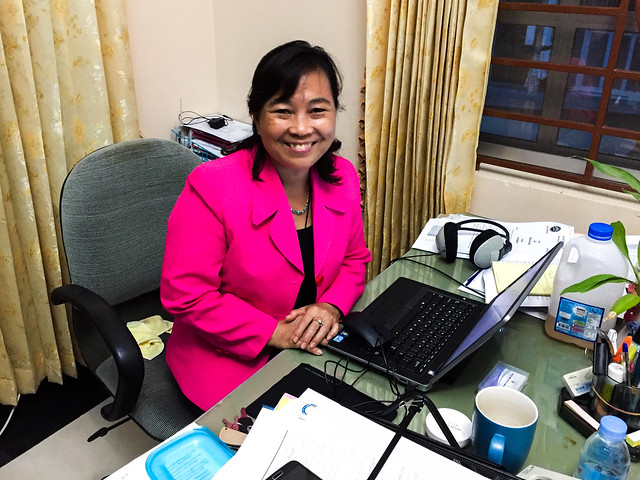

The suit jacket that Chhun Phanapha is wearing is such a bright shade of pink that it seems to be glowing. It is the first thing you notice about her when you walk in the room. The second is the aura of capability and calmness she gives off, and the third is her voice: soft and lyrical, like birdsong.

As the executive producer of the ECCC’s weekly radio show, these traits are surely godsends to the rest of her team. Phanapha leads a group of women working out of small, tightly-packed rooms on the second floor of the Women’s Media Centre, in the north of Phnom Penh. Each week they produce an hour-long audio exploration of the Khmer Rouge Tribunal.

Although she’s been working with the Women’s Centre for years, Phanapha took over the radio show just two years ago. The show first began in 2011, and after a hiatus for most of 2013 began again later that year. To Phanapha, it plays a vital role in exploring the legacy left by the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia.

“We have a lot of listeners call into our program and we have a lot of people interested in the court, and they want to know how it will continue with Khmer Rouge leaders,” explained Phanapha through a translator.

To explore this legacy, she and her team focus the show on a different topic each week, usually something relevant to what’s currently happening in the Trial Chamber of the ECCC. Each show features summaries of the witnesses in court that week, followed by stories from Cambodian citizens about their experiences relating to that topic.

But the aspect of the show that crops up again and again in conversations with Phanapha is her effort to emphasize the proceedings of the court heavily. One of the recent shows, for example, had a legal consultant from the Supreme Court Chamber talking about the upcoming appeal judgement of Case 002/01.

“Before the show, [people] didn’t know about the process of the ECCC. They wondered why it takes so long to give justice to the leaders, to the victims of the Khmer Rouge. After they listen to the show, they know the process of the ECCC,” said Phanapha. This understanding, to her, is crucial in allowing the country to move on from the trauma incurred during the Khmer Rouge era.

In a country that is still mainly rural with low levels of TV or internet penetration, radio is a vital mode through which the court can access the public and spread information on what it is doing. The show has over two million listeners – not weighted towards any age range in particular, says Phanapha, based on the callers who phone in with their comments and views.

To her, the reach seen by the show is proof of the importance of the work they’re doing. But it goes deeper than that. In a country still heavily dominated by patriarchal structures, the fact that the show is produced almost entirely by women puts it in a unique position to tap into stories and perspectives that, more often than not, stay hidden.

“Because we are women, we know the feelings of the women victims,” said Phanapha. “Women can show their hearts to us.”

In other words, she says, they can talk about rape and other atrocities they experienced during the Khmer Rouge era – ones they wouldn’t otherwise talk about.

The callers generally respond to the content of the show, and the team tries to ensure the topics covered are appealing to their diverse range of listeners. “Some programs we focus on the youth, some programs we focus on the old people,” said Phanapha. Older Cambodians often call to share their experiences that are relevant to the material discussed in the show; young Cambodians call because they’re curious about this aspect of their history.

The people who listen and engage with the show are what drive Phanapha. After two years of helming the ship, her energy hasn’t abated. She quickly rattles off specific goals she has for upcoming shows – they already do profiles of victims but she would like to do more. “Young people want to know who the victims were, who was in the Khmer Rouge,” she says.

The only constraint, as always, is money. “Our program depends on donors, so if we have funds we can do more,” said Phanapha.

For her, there’s a personal connection to the potential this show holds for Cambodians. “The program reduced the stress that I kept a long time ago for my family, because my father died during the Khmer Rouge era,” she said. “I had violence towards the leader of the Khmer Rouge, but when I work for the ECCC [show], I use an open heart to talk and it reduced the strain on my mental health.”

Phanapha now better understands the court’s procedures, so she is able to explain to the people who the show profiles, including her own family. “Especially my mother – after she listened she felt less unhappiness. She began to forget the past. It is history for the youth to learn. For the old people, they want to forget because it hurts them.”

She gestures to her neon pink suit jacket. “I am able to be colourful now,” she smiles. “I feel better.”